COMPELLING AUDIENCE CONNECTION.

"Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with meaning." Maya Angelou

Your Words. My Voice.

Who Is Susan MacNeil?

An authentic delivery makes all the difference.

Combining decades of radio and television experience with acting skill, my voiceover delivery is polished

without losing the personal feel of talking to your next door neighbor.

In the studio, I take direction well and am unafraid to experiment until the end result is perfect.

Being genuinely interested in the material as a voice actor means that the listener will actually hear - and retain - what I have to say.

If you're seeking a new voice to bring excitement to your marketing campaign, contact me today!

YOUR MESSAGE. MY VOICE.

This video, named "Pink Bike," was written, directed and narrated by me when I was the Executive Director of AIDS Services for the Monadnock Region, Keene NH. Our agency was a finalist in the 2010 Toyota 100 Cars for Good campaign.

COMMERCIAL FILES

Listen to snippets of commercials which showcase my range.

Susan MacNeil COMMERCIAL MP3.mp3

NARRATION FILES

Hear a variety of narration approaches.

Susan MacNeil NARRATION MP3.mp3

A COMPLAINT IS A GIFT - BBC AUDIOBOOK

VOICEOVER, WRITING, PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT, NARRATION, AUDIO DESCRIPTION, COPYWRITING, SPOKESPERSON

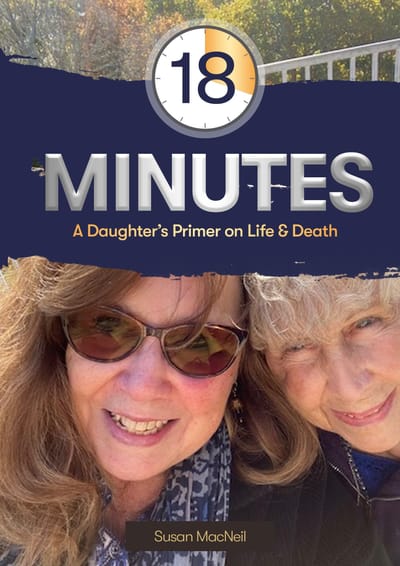

"18 Minutes: A Daughter's Primer on Life & Death" published October 2022

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1892538016

My mother led an extraordinary, ordinary life. A woman shaped by the culture of 1950s domesticity, she left a lasting impression upon every person she met. Her example of thoughtfulness and preparedness extended to my required attendance at "When Mom Dies School", despite the fact that I was a reluctant pupil. I wrote this primer as a roadmap, a gift from my mother through me to future students who would rather skip school.

Reading this book and vicariously attending "When Mom Dies School" will help prepare the reader to navigate an extremely difficult and, sometimes unexpected moment, with patience, competence and, most of all, love.

Amazon Reviews:

-“Wow... I am thunderstruck by this book. Susan, thank you for the love and integrity you expressed to chronicle this experience. You have honored your mother in such a beautiful way. Also, you have planted many seeds in the hearts of readers (such as me) who are preparing for this inevitable day.

-“Your book is practical, it is real, and it is raw. I know that many good things will come to those who read your story and take it to heart. God bless you with His peace.”

-“Susan MacNeil passes along valuable advice for preparing adult children on how to handle the affairs of their deceased parent. More than this, however, she shares a beautiful tribute to her Mom, as well as the sad last 18 minutes they shared. She makes the reader feel as if we knew Miss Jean. An unforgettable read!”

-“I've got to admit I cried through the whole book! I am 65 and my precious mom is 87. I related so well. So many loving helpful tips. Beautiful story.”

-“This book is a must-read to prepare for that inevitable day. You will be deeply moved by this story.”

PUBLICIST/CONSULTANT/VOICEOVER

Toyota Cars for Good Finalist – Wrote, produced, narrated video submission

Voiceover, BBC Audiobooks, "A Complaint is a Gift"

Voiceover, "Choosing Guardianship in New Hampshire"

Voiceover and video project, “American Nurse at War”

Radio and Video Projects

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Voice Actor training with Such A Voice

Acting & Screenplay classes with Nora Fiffer

Community Access Television Program Development/Producer

Radio Show Host, Producer

Fiction Writing, University of Vermont

John Brown Limited, Major Donor Research & Planned Giving

FREELANCE WRITER

1994-Present

"When JUMANJI Came to Keene!"

BLOG MUSING 1 ... First Kiss

Richard Bettis was the only black boy in my 3rd grade class and the entire school. Why his family moved to the rural farming community of picket fences and red dairy barns that populated my town, I’ll never know. But there he was, the class comedian dressed stylishly in ill-fitting clothes, torn sneakers, smiling a daredevil grin.

This was not a time of political correctness. Likewise, although we were a Connecticut farming community we weren’t hicks. Richard wasn’t treated with discrimination. In our 3rd grade way we revered him, so different from the rest of us. Everyone wanted to be his friend. I couldn’t take my eyes off him. He was mysterious. I longed to touch his hair, floating above his scalp like soft brillo. I couldn’t begin to figure out why it never seemed to move, nor did it occur to me that this thought could be construed as anything but wonder. His friend, Jay McCollum, was my friend too. Jay introduced me to Richard and while I secretly admired him, daydreamed about him, watched him furtively from afar, I never dreamed I’d ever have the chance to be close to him.

It was the river next to my house that brought us together. The water gurgled under the bridge, over rocks made for sure feet in canvas sneakers with crayfish lurking underneath. Boys like such creatures, and since I had 3 brothers so did I. Boys like Jay and Richard also had freedom to roam, and on one Saturday, somehow, they ended up in my yard inviting me to search the river bottom for crustacean wonders. In my pink gingham shorts and matching sleeveless button down shirt with the Peter Pan collar, I accompanied them under the bridge. It never occurred to me there was an ulterior motive nor that Richard returned my nervous desire for connection. It was Jay who boldly asked me, while sloshing barefoot next to the cool underside of the bridge, if I’d ever been kissed.

“No, I have not,” I replied. We all laughed nervously. I remember how damp the air was on my bare arms, how aware I was of the darkened underbelly of the bridge, how Richard’s eyes were as black as his skin.

“You wanna?” Richard asked. My ponytail, one very long curl that began at the top of my head and bounced down past my shoulders, the pride of my mother’s hairdressing skills, shook as I moved my head side to side. Deliberately, I responded, “No, I do not.”

Richard stepped closer to me. “Yeah, you do.” In his best bad boy style, he grabbed my arms and pushed me up against the wall. I wasn’t afraid and stared right back at him into those mesmerizing eyes without flinching. “Do, too,” he repeated. “Do, too.” He pushed me back into the cement bridge and the grit braised my left shoulder. I turned to see the mark it left and he placed his hand over it, while at the same time muckling onto me. His lips felt foreign, soft and very full, and I kissed him back because, as he said, I wanted this curious moment. As lightly as possible I touched the top of his afro, unlike anything I’d ever seen or felt before. I remember thinking, “Stop moving your head around!” Without any fear I went with the flow, a rough first kiss from a rough boy who had no business being in my boring white life.

In that moment Richard became a delicious secret, my first kiss with Jay as voyeur. “Told ya!” Richard preened in his best bad boy fashion before heading to the rocks and our original intention. I smiled broadly, he grinned and we locked eyes. I remember the river was cold, the rocks slippery and we caught a pail full of crayfish. There was no more talk of kissing. We had fun. And I’d satisfied my tactile urge to touch his hair.

Today little girls are warned that this kind of behavior is inappropriate, which, of course, it is. But these were different times, and back then this subject wasn’t on a 3rd-grader’s mind. I had friends who were boys and girls. We all played in the river. It was rural life at its best. We were classmates and neighbors. I wasn’t afraid.

Once I was a teenager, I had more to fear from the college guy who unceremoniously took my virginity while Raquel Welch looked down from her One Million Years B.C. poster on the wall. Not long afterward he dumped me, worried that I was underage and could ruin his life. At least Richard celebrated an unspoken desire to innocently experience my first kiss with the new boy in school. I never found out if I was also his first kiss, but given his level of expertise and delight I’m thinking probably not.

Years later I would find him again, embodied in another black man who became the love of my life and then broke my heart for all the best wrong reasons. And now I know for certain that Richard’s first kiss and its unfulfilled promise will haunt me with the singular memory of awakening to desire.

BLOG MUSING 2 - MEETING VIRGINIA

Each morning I greet Virginia as she scrutinizes me from the living room wall. I found her upon leaving Miss Krystal Kenzington after enjoying al fresco coffee and conversation. Krystal had arrived the night before as handsome Ray, silver-haired, well-heeled man about town, not the blonde bombshell who commanded the stage with dangling zircon earrings. We dished at length over coffee and Bloody Mary’s about the difference between living her life as Krystal versus a man who held an executive position at a major bank.

Our pensive morning-after conversation turned to the examination of her existence in and out of drag. She was pushing the corporate landscape to recognize her transition to heels and dresses as well as pronoun and name change. She didn’t care if it made the status quo uncomfortable. Krystal was a trailblazer who knew her strength and didn’t give a fuck.

She'd performed her best-ever Liza the previous night at yet another agency fundraiser. Her dedication involved travel from Providence to rural New Hampshire in support of my AIDS service organization. Watching from the audience, I found myself aroused by the inescapable allure and power of this female archetype. Ray insisted on picking up the tab, leaving $40 for a bill not quite $20.

“Important to tip well. Karma, after all.”

We strolled down the sidewalk locked arm in arm and as we passed an art gallery I glanced casually into the window. That was the moment that Virginia beckoned. “Krystal, look at this. Look! Isn’t she gorgeous?” Ray peered into the finely nuanced profile. He pointed out that it was a lithograph of Virginia Woolf who, apparently, was calling out to go home with me.

“You’re a writer. You read her work. She wants to hang out with you, I know it. So buy her whatever she costs. Now give me a smooch before I hit the road.” I planted a kiss on his cheek and then locked his lips on mine, coming up against a night’s stubble when just hours before only air kisses were permissible so as not to muss the transformation.

I stared hard. Virginia Woolf, indeed. Was she calling to me? Did she and I have something to talk about? Her red blouse stood out in contrast to the otherwise muted palette. The frame was just ornate enough not to detract from the determination in her eyes. I needed some of that directive, her surety. I wanted to live in that feminist room she described in 1929, the one that she believed all women deserved, so ahead of her time. “Walk in,” she was saying. “Meet me. I’ve been waiting for you.”

Displayed intricately in the very front of the window, it took the owner serious effort to remove several layers of other work lined up behind her. “She belonged in the first row,” he explained, and I nodded in agreement. My breath was shallow, my heart began to race and I could feel the tingle in my fingertips when he finally reached the frame. The flush of excitement made my face hot. “Here, hold her,” he said placing the gold border in my hands. “See what she has to say.”

Containing my enthusiasm I played it cool, casually taking my time to shift from his grasp to mine. And then there she was, a reluctant mentor sizing up a new pupil. Without removing my gaze I asked, “How much?” Krystal’s word were ringing in my ears, telling me to buy her no matter the cost. I began to calculate what I could realistically afford, determining that $500 was my top dollar.

“Well, it’s a nice piece. Signed print. Artist lives around here. You can find him online.” Pause. “She can go home with you for $250.”

Snap! Ever so carefully I placed her on the counter, a supreme feeling of satisfaction building on a cellular level. I couldn’t rip the check out of my checkbook fast enough. The owner offered to “wrap her up good.” Yes, I thought, wrap her up in Chinese silk worthy of Virginia’s brilliance, just like the finery of her red blouse. “Congratulations. That’s an excellent piece. Enjoy.”

I nodded, smiled, and walked out into the sunshine with her under my arm, then shifting to a full embrace. “Hello, Virginia. I can’t wait to get you home,” I said aloud as my lips grazed the brown kraft wrapping. A young kid passing by heard me and grinned, like he knew my secret. It wasn’t at all odd to him that I was speaking to some unseen treasure. That is the beauty of youth, the magic that I’d left behind long ago, when everything was possible.

During the first week of her relocation to my space, I ceremoniously seated her so as to lounge in an overstuffed chair. After all, this was not a process that could be rushed. Virginia’s place of honor had to be just right. I moved around other framed pieces to accommodate her presence. I brought her to therapy with me so she could be introduced to another wise woman whom I cherished. She even spent a day in my office for no other reason than that I missed her when we weren’t together. More than challenge and inspiration, more than a reminder that I needed to find a room where writing mattered, I loved her. I’d always loved her, devouring my dog-eared roadmap of A Room of One’s Own since 1989 when, at age 36 and much to the dismay – no, outright horror – of my husband, I cashed in my 401K and bought my first computer so I could become a writer. Three years later I left him and my old life behind. I think of this threshold as the beginning of personal freedom and independent thought, where every room now became my own.

But ripening cannot be rushed, like grapes on the vine, and every skillful winemaker knows exactly when the transformation must begin. Twenty years after discovering her wisdom on the printed page, I found Virginia in the gallery because it was time. And almost one year after coming home with me, we’re finally ready to begin talking. Virginia and I, we’re going to peel us some grapes with instruction from that great jazz standard by Anita O’Day. We’re seeking only perfect globes in hues of green and amethyst, at the peak of perfection, warmed by the sun with lusty intention. We’re going to intrude on my exhausted yearnings and fears, desires and tragedies. And then we’re going to rip off the protective skin and crush the pulp between our teeth, catch the juice running down our chins with our tongues in the manner of everything sensual. We are women. We deserve nothing less.

“Peel Me A Grape” was the first published song by Dave Frishberg who wrote it as a “cute, sexy piece.” But gritty jazz singer Anita O’Day made it so much more than a forgettable ditty. She knew how to growl, slinking the words into a fine vintage. Isn’t this what Virginia was saying decades ago… that women demand depth, freedom, luxury, attention, love?

Peel me a grape, crush me some ice

Skin me a peach, save the fuzz for my pillow

Talk to me nice, talk to me nice

You've got to wine and dine me

Don't try to fool me bejewel me

Either amuse me or lose me

I'm getting hungry, peel me a grape.

Room was a compilation of college lectures penned by Woolf in which she mercilessly insists that women writers rise above flaws and limitations. She undeniably states that women are inherently powerful, hardly at the mercy of the dominant male paradigm, and that we deserve the right to our own genius and freedom. Woolf believes that women must approach their art as a ministry that feeds the souls of whomever reads the words springing from our depths. We must love the sensuality of language and feel the sting of criticism, massaging our egos to produce valuable work while losing our need for self-righteous indignation and rage in the balance. She suggests that empathy for others, even those with whom we disagree, can co-exist with appreciation of joyous experiences in our lives, for without them we cannot possibly value and discern the difference.

Are things really so different today? On the surface, we would quickly conclude that those days from the beginning of the 20th century are long gone, that women continue to rise above their proscribed ranks and have more opportunities today than ever before. Although true in some ways, the pushback from the 21st century version of Republicans-Gone-Mad is, in part, an effort to get us back into our cages like good girls. We can have a room of our own, but only if we promise not to do anything that isn’t approved by God and church. So today we are hampered with the same challenges faced by Woolf and our response must be as courageous. She wrote with guts, not weak-willed new age crap. She would not have dreamed serving up pseudo-psycho babble or trendy catch-phrases. For instance, the understanding of grace and power would never be co-mingled as something silly called the Grace Wave.

She was blunt and truthful in challenging every notion about what it meant to be a deserving woman in a male-dominated culture by holding up a mirror and staring squarely into the reflection. Who says you are beautiful or plain? Vain or humble? Smart or stupid? If it’s a man, better think twice about the validity of these conclusions, because chances are a woman would see that same countenance differently. Women can see in the dark, navigating perilous channels by a magical sliver moon. Like wolves, we howl with the power of lunar madness.

Here I am, almost 70 years old. I met Virginia when I was 58, and it has taken me a decade to believe in my right to love words. I have a room of my own, a life of my own, independence, enough money to get by. I’ve been working on developing clarity and boundaries and understanding about the experience that’s delivered me to this very moment. So why do I stumble when it comes to completing my own work? What is the depth I need to plumb in order to find the dedication and burning desire to write? How do I bring my own reserves of time and energy into balance so that I can earn a living? How is it possible that my grandmother’s hope chest barely closes for the lifetime of uncompleted masterpieces that clamor impatiently for my attention? Decades of words on a page that do not see the light of day.

I must unearth my own roadblocks, but haven’t known how. Perhaps, as Woolf believes, it’s that the two sexes of my mind are not willing conspirators in bringing their progeny into the world. In order to be survive, I’ve been taught to compartmentalize and multi-task and entwine the threads of disappointment and joy into a threadbare patchwork. What of the trembling under this creative blanket because it’s not warm or strong enough? How do I drape it around me with the simultaneous need for reinforcement? Perhaps the problem is, as Virginia tells us, I’ll see a likeness that disappoints, a hope chest that isn’t full of promise, and I will shatter in the illumination of my own cowardly dereliction. After all, women are supposed to be grateful for crumbs.

But I’ve had my share of leftovers, an unfulfilled appetite. I desire the full-course meal to satiate this undulating craving for more. I’ve reached that pinnacle where my internal desperation is a greater motivation than fear. If Virginia and I hold hands, I trust that she’ll guide me through this unveiling, peeling back the protective veneer to expose a spongy underbelly with resolute purpose. Yes, Virginia and I are going to strip bare some grapes by examining the words I’ve hauled out of cedar-lined obscurity, having been unceremoniously crammed in the shadows for too long. It’s not so much that I feel like I’ve strode into the light but rather that I’m willing to let my eyes adjust to the uncertainty of darkness, where the answers to my dilemma reside, deep under that dilapidated refuge of fear that the room of my own isn’t big enough to hold the anguish and tenderness belonging universally to women.

BLOG MUSING 3 - TWO FUNERALS

Rosie

75-year-old Rosie wore tan polyester pants and a leopard spotted sweater to her husband’s wake. It was a Tuesday, and although she normally had her hair done once a week on Wednesdays she did so early in honor of the occasion. Like a restaurant hostess, Rosie smiled broadly at each guest as they entered the funeral home, her face a brighter shade of pink than usual due to the excitement of it all. Rosie and I worked together and she greeted me enthusiastically.

“There were probably 200 people here, even a whole group from the fire department! He was a firefighter, you know. My Romy, he was the orneriest cuss when he was alive, but everybody loved him anyway. Isn’t that right, Lucy?” she asked her youngest daughter, much smaller in stature than the rest of the family. Lucy, mouth quivering, nodded obligingly. Indeed, the town turned out to recognize a home-grown boy, his family having moved no farther away than 15 miles down the road.

It was a motley crew who assembled in front of the closed casket, more of an afterthought than the reason for such a somber event. Small groups chatted and laughed and slapped each other on the back while Romy lay in the dark. I sat in a metal folding chair and said a prayer for this man who was so hard and mean that he refused to let his wife put another outlet in the bedroom when their appliances warranted it; who didn’t allow any changes to his routine or house, ever, not even moving one stick of furniture from its appointed site. One of the first things Rosie did when he was admitted to the county home, when she knew he would never walk through the door, her door, again, was to hire contractors to rip out the ancient bathroom and give herself a decent toilet. She then moved her efforts into the kitchen and installed new flooring to replace the dark, stained, torn piece that she had labored to clean through four decades of children and holiday dinners. Finally the electrician arrived, alleviating the fear of fire that had haunted her because of the highway of extension cords that snaked around the perimeter of her home.

I joined the line to pay my respects just as Rosie was busy reminiscing with old friends, commanding center stage attention. It bothered me that she was unaware her left pant leg was caught up in her winter boot but she was busy making a point. “You were lucky to get 10 cents a quart for strawberries. I remember when I was twelve years old and got 2 cents! Two cents! Saved up all those pennies for one whole summer and bought myself two new dresses and a ukelele.” I gave her one last hug and headed for the exit where the two men who owned the dimly lit memorial chapel, consisting of fake wood paneling, plastic flowers in recycled vases and a vaguely medicinal odor that I didn’t want to think about both raced to get the door for me.

The sharp cold night bit at my ears. I wouldn’t attend the funeral tomorrow, but knew that Rosie would be satisfied to see the fire department turn out in their dress blues no matter the weather. Rosie gave herself only one day off after the funeral before returning to work. She did not appear glum or sad; in fact, her greeting was bright and the customary spring in her step had not faltered. Rosie was all business as I offered my condolences once more and the chance for her to go home, but she quickly rebuffed my suggestion.

“No, thanks. No need of it. I’m fine here. We all expected he wouldn’t last long once he went to the home. What I need to do is get back to work. I still have a life, even if he’s gone!” Her perfectly coiffed head bobbed emphatically as she made her point.

“Well, if you need anything, just ask,” I replied. She acknowledged me with a smile and said absent-mindedly.

“By the way, I may get a call from the painters. I’m going to have my kitchen done over.”

Adele

Eternally optimistic, Adele at almost 80 rarely complained and saw only the best in others in order to maintain a sense of denial amidst her sunny disposition. Her first marriage lasted 30 years and this second one of 25 years was to a man that everyone, including his children, knew to be a son of a bitch who only became more controlling and miserable as his illness progressed over the course of five years. He died in agony and went quickly, mercifully, not so much for him but for her. She’d suffered enough having spent over half her life being married to disappointing men.

The piece she wrote about her husband for the minister was in her usual positive outlook, focusing on his good qualities that were somewhat true. When the invitation was issued for a family member to come forward and offer a remembrance or two, no one moved. And so the minister resorted to what Adele wrote as a eulogy, words that she never intended to be read aloud but had written with such generosity that it appeared otherwise. Someone sitting amongst his children snickered to hear a description of a man he or she did not know, selfish behavior that embarrassed his grieving widow.

After the funeral she showed me his garden outside the back door, a raised bed that could be reached from his wheelchair. I wondered if he knew that last summer’s garden would be a final effort. An old metal antenna was stuck in the bed as a post for his tomato plants, which produced a mighty yield. I resisted yanking it out as a way to assert the fact that he was finally gone. Sitting around the kitchen table moments later, she took a sip from her water glass and cleared her throat.

“Poor John. I imagine he knew he’d never work in the garden this year.” She paused in consideration of her next thought. “Well, there’s one thing you can say about him. At least he knew how to grow good tomatoes.” Months later on Father’s Day, she visited the cemetery and was pleased to see that his children had erected the headstone. She spread a blanket on the ground to plant two items; a bouquet of silk flowers she assured me were so high-end that even a botanist couldn’t tell they were fake, and a tomato plant.

BLOG MUSING 4 - POWER & LOVE: TWO SOUPS AND A HOT BALL

When I walk into a prison or jail to visit with a client, I’m aware of the ultimate paradigm. Power is the decisive common denominator, the hostage-taker. Everything is about who has power and in what setting, and if you don’t believe that then you’re not paying attention. Doesn’t matter if this concept is applied to a marriage or work relationship or celebrity status or being locked up. It’s what Virginia was saying when she demanded that women have a room of their own, thoughts of their own, decisions of their own. Virginia knew that power imbalance deadens the spirit and mind.

Power perceived and assigned by others can take you off-guard. I felt this firsthand when I became unexpectedly famous in my laundromat. Presidential candidates swamp New Hampshire every four years to conduct obligatory town halls and handshaking campaigns. They visit the locals on their own turf, pleading for votes by being just as ‘down-home’ as anyone else. Since I had been in touch with the Obama campaign office in Concord regarding the subject of AIDS in a rural setting, I was invited to meet the man personally. Although I didn’t run out to buy a new outfit or get my hair done, I admit to seeing stars.

Each of us was invited to ask one burning question of him and I spent considerable energy crafting mine. Our assignation was to take place at Lindy’s Diner, where every Presidential candidate has come for decades to shake hands amongst the locals. All across NH, hopefuls make sure they hang out in diners. It’s as though the nostalgia associated with these eateries represents their own unique room, supposedly full of just plain folk speaking just plain conversation. Obama’s people had planned a rally in town that day and we were told we had 30 minutes prior to the event for the six of us to chat. I surveyed the diner’s outdoor patio, worn plastic tables and chairs with sharp edges, the frayed umbrella, flowers drooping in the midday sun. Couldn’t get more down-home than this.

Bedraggled media types mingled with buttoned down secret service guys around the perimeter. Expectation was in the air as we introduced ourselves to each other and waited for the man to appear, which he did without fanfare. White shirtsleeves rolled up to combat the heat, no signs of sweat or worry, our future President strolled in the way that men who are long and lanky so casually do. His smile was a spotlight that drew us to our feet. I was the first one to move toward him, hand extended, smiling, and heard the cameras snapping. We sat around the table in our unforgiving plastic chairs, a mere 4’ away from him, aware of the magnitude of our good luck.

After a brief preamble, we began to engage. Pieces of paper appeared with our thoughts and questions. We did admirably, six different subjects explored one on one with our candidate. And he remained for a full hour, which I’m sure screwed up his schedule. But we were articulate and he was interested. Before he left we each got to put our arm around his waist for the official photo op. That moment was thrilling for two reasons. We all believed he would win the nod and forever we’d have the story to tell about hanging with the future President of the United States at Lindy’s Diner. But more important to me was the feeling of a deep sense of equality. He did not stand on ceremony nor was there any bullshit in his responses. He had an air of intelligence that did not usurp our place at this meeting or threaten to turn us into tongue-tied sycophants. Instead he expected us to operate at his level. The opportunity was as clean as the day was bright.

My photo appeared in the paper, page 3 above the fold, a large black and white. It wasn’t bad but neither was it Pulitzer Prize material. It generated lots of commentary and made me happy that I’d had the honor of this experience to recount, but hardly placed me on any pedestal. Or so I thought until that day in the laundromat. One practical, guilty pleasure I allow myself is dropping off a laundry basket full of dirty clothes and hours later picking up my items clean and crisply folded. It was about a week after the Obama photo ran that, as usual, I walked into my laundromat ready to dump the basket on the counter and head off to work. Fans were swirling fetid summer air in an effort to mimic relief. I was aware of something fluttering on the wall to my left as I entered but paid no attention as I smiled at the owner, a pleasant Oriental gentleman whom I didn’t often see at the cash register.

“Morning,” I said.

He put down his book, stood up, a look of realization on his face. Smiling broadly he said, “You famous! You our customer! Famous!”

“What?” I replied, completely stymied.

“Look! There! You famous! Obama!” He pointed over my left shoulder and I turned to view my newspaper photo tacked to the wall. I felt sick to my stomach.

“Oh, thank you, but no, I’m not famous. Really.”

But he would not be deterred. “Yes, you are! You with Obama! Famous!” I thanked him again and got to the business of my laundry before more undeserving accolades came my way. I left conflicted about what happened. Although I appreciated the owner’s delighted response, there was a disconnect between our interpretations of the event. The sense of equality I’d enjoyed had been hijacked. The owner’s attention was personally uncomfortable, and when I told others of my dismay their reaction was to consider the owner pathetic, which wasn’t at all the point. I didn’t join in the chiding because I’d seen the look on his face, so proud of his connection to my 15 seconds of fame. Between July and September I watched the newspaper image fade as the edges curled around the clipping. Enough, already. I finally asked him to take it down and a week later it was finally gone.

Every day is about power, inequality and imbalance in all kinds of systems, but this is a 24/7 reality if you’re incarcerated. Otherwise meaningless items take on great significance. Access to the commissary is everything, providing barter items that help to assign inmate pecking order. To combat prison food, packages of peanut butter crackers, candy, chips, pork rinds, hot sauce and other goodies become gold. Of course, you can only order from the commissary if someone on the outside makes sure you have money in your account since a prison job pays $2/day and these funds accrue until the day of departure. Inmates who have no one to provide for their needs eat processed cardboard and stale sawdust and soggy messes with an aluminum aftertaste.

It’s easy to translate this same dynamic into personal relationships. Without the honor of a room of our own and its inherent authority we become trapped, an inmate lacking commissary privilege. My clients tell me unbelievable stories of the world that exists in prison right under the eyes of the guards who more often than not perpetuate the system because it helps to keep inmates in line, thereby making their job easier and assuring their power grid. How is this any different from a domineering workplace where favoritism and discrimination is rampant? Or a family run by its bullying overseer? When deeply held desires and values collide against abusive authority, we might as well be behind bars.

I asked a client for help the other day and he replied wryly, “Two soups and a hot ball.”

The currency of power is a tightrope bargain.

BLOG MUSING 5 - RIPENING ON THE VINE

The hard reality is that women are hard on women. We don’t forgive our mothers, partners, best girlfriends or daughters easily. Or we do just the opposite and forgive every trespass because we demand less under the guise of being understanding. For we can relate to one another’s hardships, inequitable treatment at the hands of others, sacrifices, longings, heartaches. Older women who wish to serve as mentors often find a less than enthusiastic audience among younger women, our tutelage undesired because they are lazy in the way that 21st century women have come to expect their lives to unfold – with relative ease and a certain innate entitlement. I speak, of course, of young women who may not have their emotional needs properly met by their 40-something parents but don’t go to bed hungry or wear tattered hand-me-downs. They have not been provided a good example because, simply put, women of my generation did not do a good job of raising their children.

I refer to those of us who came of age in the 60s, believing that our darlings were the center of the universe. It was a given that they could no do wrong but if they did behave badly, it was someone else’s fault. We raised men and women without the desire or capacity for introspection and, thus, the inability to own their flaws while marching toward the alien concept of redemption. It’s easier for them to place blame outside of their personal shortcomings than it is to look inside, regardless of whether that blame is shouldered by a grandparent, husband or wife.

Think of the analogy as that perfect glass of red wine you crave after a long day of negotiating your time and energy with the world. It sits in the oversized bowl like a waiting jewel. Your fingers caress the foot before they travel up to the stem to the base of the bowl to swirl the nectar and watch for the telltale sign to appear, leggy rivulets clinging to the interior like a Rockette’s high kick. This luxurious signal of a good vintage makes your mouth water with anticipation of intense flavor developed in an aged oak barrel. Just as each family has a unique geneaology, so does a bottle of wine begin with a choice between 10,000 kinds of grapes, particular characteristics pertaining to size, acidity, skin thickness, color and yield per vine. Only an elite group, referred as noble varieties, will ever make it into your glass and over your tongue, having first been gingerly babied on the vine, exposed to just the right sunlight, climate and tender loving care to assure maximum drinkability. Peel these grapes and the fleshy fruit is beyond luscious, borne of ancient Mesopotamian vines hand-carried from the old country in muslin cloths to Australia and California.

But not every vinter has these resources available to them. And so some grapes end up on the sale rack at the liquor store, that $6.99 bottle we tell ourselves is good enough because we just want a drink. If we advise our children that despite their flaws we love them without simultaneously encouraging them to evolve into a more perfect grape, how can they be to blame for a lackluster life? Peel this particular fruit and find a mushy mess that once held promise but could not measure up without proper oversight, the result of errant winemakers settling for less. Focusing on one’s inadequacies can feel intolerable. Being raised in relative comfort meant that development of conscience is stalled. And so this generation doesn’t understand the beauty in remorse, the certainty that we cannot live fully in the light unless we know darkness, the importance of repentance.

Pity these children and how we let them down, withering on the vine. Maybe you don’t agree, have had a different experience, but statistics tell the broader tale. Of all women, I am most hard on me. So what of my generation? How did our mothers raise us? Often it was with relative silence. There weren’t deep conversations around the dinner table. Our fathers often worked shift jobs in factories and there was no nightly dinner table unless your dad had a white-collar job. By the time I got home from drama club and cheerleading and 4-H variety shows and sleepovers and after-school job and visits with my boyfriend, I walked through the door into the emptiness of my kitchen. The dishes had been done, the room was clean and my meal was in the frig, either cooked or left for me to prepare with a note taped to the plate. Mother was asleep and so were my brothers. The avocado green appliances taunted me with their inertia.

I became used to quiet, to my own thoughts and depth was available in books written by Rod McKuen and Kahlil Gilbran. I did not have a tutor, a mentor, nor did it even occur to me to ask. I turned inward without guidance and did the best I could to create a belief system based upon my internal and external worlds. After all, you only got help if you were that girl who was wild or loose or stupid, black marks against your soul. The rest of us were expected to make our way with blinders intact. My mother taught me kindness and generosity and the certainty that she was my mother forever, the one person who would make sure my cheerleading uniform and white socks and sneakers were clean for each game. But beneath the beautifully frosted cupcakes awaiting us after school, I also witnessed her self-sacrifice and self-deprecation in the role of mother to her children, despite the bright smile.

I didn’t know what to name it then, but in hindsight her lack of assertiveness and independence was due to the fact that no-one expected her to do anything else. She was there to serve. Clearly that is just exactly what I believed. She did not even consider having a room of her own. She ran and ran and ran until she ran with my brother’s Flexible Flyer into the window of the shed at 2am, smashing the glass with a primal cry. I tore downstairs and out the back door to see her being restrained by my father. I never forgot that moment, where I was told nothing was wrong and to go back to bed when it was clear that something was plenty wrong. But the incident was instructive. I witnessed what happens when women who believe they are supposed to bury their burdens deep within can’t stand it anymore. Only then was it permissible to visit Crazytown.

Throughout my 13th year I had insomnia and night became my ally. All I knew was the intolerable sensation of being afraid in the dark, alone, and needing to find the light. Eventually I would creep downstairs to the first-floor stairway, close the door to the landing, grab a green Funk & Wagnall encyclopedia with that distinctive pebbly finish, position my slippers on the stair below me and read. Any volume would do. The pages were barely breathing as they turned in my hand and I read about subjects that had no reference in my waking world but became my universe night after night when unknown secrets revealed themselves to me. When I reflect upon this regular occurrence, it is remarkable to realize that my parents did not feel my tender presence crouched on those hard plastic stair treads, wriggling every so often to avoid discomfort and massaging the balls of my feet into the surface as if to ground me. I stayed there until my eyes were finally ready to close and marvel that I was able to manage school on so few hours of sleep, still an over-achiever and everybody’s good girl despite the clutch on my heart.

That clutch. A physical sensation that felt as though someone was literally squeezing my heart, wringing out love, fear, doubt, confidence. The first time I recall thinking my heart would stop beating was in first grade, when my teacher told the entire class that I was in charge while she went to the principal’s office. Who told her I wanted this attention, this responsibility? Sure, I scored 100% on the standardized test and my mother said everyone thought I was a very, very smart girl, and maybe I would skip first grade entirely, but that didn’t mean I was a grown-up. All eyes were on me to see what I would do or say, but how could I react when my heart was about to collapse like a deflated balloon?

I just stared at my desktop and prayed that I would not die in that moment. I recall the red plaid dress I wore, my long dark hair in one huge ponytail curl, the tops of my white socks folded over neatly. I have no idea how long she was actually gone from the room, but that is my last memory of first grade.

In second grade, one singular memory still embarrasses me. I was at my desk and the math lesson being taught by Mrs. Davis was lost on me because I had to pee. I mean, I really had to pee. I hadn’t visited the girls’ room after recess like I was supposed to and now I was in trouble. It was my fault because I hadn’t been a good girl and followed the rules, so in no way could I raise my hand and ask to go to the bathroom. Finally, when I couldn’t stand it for one more second, my bladder let go. I have no recollection of what I was wearing, but the sensation of warm urine pooling in my seat and then running down my left leg remains horrifying to me.

It collected in the top of my sock, around my shoe. Oh. My. God. I looked up only once to see my teacher’s look of horror equal to the shame I felt. She was old and smelled like sachet. “Susan? Did you have an accident?”

An accident? No, I didn’t scrape my knee, fall off my bike, trip on the stairs, cut my finger with a knife, drop something heavy on my toe. I fucking pissed my pants. This was no accident, it was a necessary release. I couldn’t meet her eyes. She did not put her arm around my shoulder or quietly say, “Come on, honey, let’s take care of this. It’s all right. I’m here.” She stood in the front of the classroom and repeated, as though I hadn’t heard.

“Susan? Susan?”

It was only when I began to cry that she was inconvenienced enough to act. She walked over to my desk and stood there. “I guess you better go to the nurse now.” That was it. Instruction. We were, after all, in a classroom. She didn’t even bother with the wooden hall pass that authorized our classroom absence, that’s how much she just wanted me to go. I was very much aware that she stood outside of the pee circle around my feet. I got up, dress stuck to my legs, and squished my way out into the hall. That’s when I really began to cry, running toward the nurse’s office all alone, shiny linoleum beneath the slippery bottoms of my shoes.

By now the urine had gone from hot to cold. I shivered into the nurse’s office, a kindly woman who didn’t hesitate to put her arm around me and call my mother. Of course, my mother didn’t even have a license then in 1963 and so my father had to pick me up. This is where the trail goes cold, for his lack of warmth was on par with Mrs. Davis. The last thing the nurse said was, “It will be okay, dear.” How I ever walked into the classroom the next day is not a conscious recollection. But that sensation remains, filled with the remorse and self-loathing of a young girl.

That’s what women do. We retain everything. Each significant event, good or bad, is imprinted so deeply on our souls that we cannot possibly escape the visceral remains. Although it is possible to unpack these experiences, dissect the trespass or joy, and figure out where to store it, those sensations never leave. I can only imagine what my mother was feeling when she experienced the release of the sled’s sharp metal rung crashing into the glass, heard the tinkling sound of the vicious shards. Did she worry she would be cut? What was so intolerable for her that she had to break something, anything? Of course, she was thoughtful – she went outside so as not to disturb her sleeping children because no one should witness her shattered psyche. Had I not been an insomniac, I wouldn’t have heard a thing. But I did. Another moment etched, a tributary on the roadmap of my soul.

Years later I asked her about that night. She said that two things converged. She was very distraught over her father’s recent death and the neighbor had put a cow-bell on their precious bovine. The cow also had insomnia and would roam the perimeter of the barbed wire fence, pacing endlessly. On this night, she had been driven over the edge by grief and the hollow sound of the bell. I wondered why she didn’t just call the neighbor and ask that the bell be removed at night. She said she tried, but the neighbor’s abusive husband would have none of it. Too bad if that MacNeil woman didn’t like the bell and too bad if his wife didn’t like his answer. It was his house, his yard, his cow. Period. Would have been nice if my father had supported her, but this was never in his repertoire.

I’m sure what she told me is true, but her lack of introspection about power, control and desire provided me with the definition of helplessness. Deserve a room of her own? Never. Years later, at the age of 78, her second husband died and for the first time in her life she lived alone. We shopped together to decorate her apartment and during these years I became her devotee. Reflecting upon all she did for us as children, I now had the chance to spoil her. Our relationship grew ever closer, and she finally claimed a room of her own with independence and appreciation, marveling at how her time was now her own. She found peace in the silent early morning hours, rising to have a bowl of ice cream and read the paper at 2am, or warm up dinner leftovers for breakfast. That silence. An unalterable catalyst in any situation. Sooner or later you have to unearth your own voice or dissipate into thin air.

BLOG MUSING 6 - INSISTENCE: THE DEMAND OF FUCK

Sometimes there is no other word. I’m not talking about the literal act, but the versatility of these four letters… specifically, when used as a single utterance. It’s when energy demands attention. It’s when options disappear. It’s when the restrictions of time and need collide to create an intolerable situation. It’s when being in relationship becomes impossible but we fight to hang onto that slender thread. It’s when boundaries cannot be found, where respect and joy are replaced with being pissed off beyond belief. It’s when shattered longing screams but isn’t heard. It’s when comfort and solace have dropped off the face of the earth. It’s when happiness and love and surrender dovetail to create an avalanche of indisputable knowing. It’s massive, limiting frustration.

As kids we didn’t have this word, not like today’s generation. They throw around the F-bomb as though it was nothing. On one hand, I think this is healthy. Removing the mystery either creates ambivalence or thrust. It then becomes just another utterance and loses its power to shock or harm. But when the language engine is revved, fueled with emotional nuances, it is one powerful motherfucking word indeed. At the core of its use in any manner is an inherent insistence. You can’t ignore Fuck as an anthem, a demand, a disappointment. Without any explanation, the listener can pretty much interpret what’s going on in the context of its use. Four evocative letters, tiny words encompassing huge emotion. I wonder who set it up this way? Love, Hate, Kind, Fear, Shit, Damn, Kill, Suck, Poor, Rich, Best, Hell. Four-letter declarations that say it all.

We look to our childhood to inform our adult experience. This can have unexpected consequences or become dry discourse. If only we could be adults revisiting our time on this earth as kids. That adage, “If only I knew then what I know now” is actually backward. I think we need to more fully understand what was happening to our young minds and hearts, changing the tense to read, “If only I knew now what I knew then.” For how many decisions in our adult lives would be better informed if we recalled those instructive moments of youth, when we trusted our instinct and didn’t need to have words? When we knew that it was magic to wiggle our toes in the river, cupping crayfish in our hands for close examination? Or plunging our face into that same water for an ice cold drink and then letting rivulets drip down our cheeks? When we acted on impulse and didn’t know if it was right or wrong? Sure, we made mistakes and drove our parents crazy and took risks but didn’t understand the danger. And sometimes things would go wrong, maybe even tragically. But we lived in the moment, in the present, in our bodies. We weren’t detached adults who intellectualize every feeling and situation in order to kill the import.

When my 5-year-old brother leaned over the edge of the bridge embankment, running his blue mitten over the surface sand just to watch it fly down toward the water like granular paintbrushes landing below in patterns and sound, he didn’t know he was in danger. I knew it and told him to stop, to get back, or he was going to fall. Another moment where today I immediately recall that feeling of dread, the big sister knowing that somehow I should be preventing him from doing this but not having the authority to stop him. At my final - Stop It! - he leaned too far and lost his balance. I screamed while watching him do somersaults toward the rocky, icy bottom 20 feet below.

I ran into the house calling out, “Billy! Billy! Billy fell into the river!” And then I went back outside to survey the damage. My mother came flying out after me, and there we saw him in his navy blue snowsuit, wearing one of those side-snap hats with a little brim, his blonde tufts curling out from under it, bogged down with his wet snowsuit preventing his gait from carrying him up the hill to the driveway.

He wasn’t crying or yelling. He said only one sentence repeatedly. “I have boots in my water! Boots in my water!” It was a tableau with motion, me watching him at the bottom of the hill, my mother straddling the icy ground to reach him.

“Don’t fall!” I cried, imagining that they both would be in trouble and me still not knowing how to be in charge. She brought him up the steep incline somehow and then called the neighbor for a ride to the hospital, because she could not drive and even if she had a license in her wallet, my father was already at his second-shift factory job with the car. So Mr. Glenney, good Samaritan, arrived promptly and off we went.

Billy had broken his arm, miraculously avoiding all the other horrors that could have equally occurred. Had his head landed on the rock instead of his arm, this might be a very different story. But it didn’t, and I was not punished because he fell even though I was supposed to be watching him. I made sure to tell everyone that I was watching him, warning him repeatedly to stop, but brothers don’t listen to sisters and it wasn’t my fault. If I had known the word Fuck then, you can bet I would have screamed it.

Contact

- Bellows Falls, Vermont, United States